All articles

Inside the 'Mentor-as-Leader' Model Multiplying Forces in Facilities Management

Clayton Mitchell, SVP at Yale New Haven Health, explains how data-driven technology is driving the shift toward a "leader as mentor" model in facilities management.

Key Points

The rise of data-driven technology on the front lines is causing leaders to shift toward a "leader as mentor" model that empowers employees.

Clayton Mitchell, SVP of Corporate Facilities and Real Estate at Yale New Haven Health, explains how the new approach elevates frontline workers into strategic partners.

Central to the philosophy is psychological safety, which leaders can create by taking responsibility for failures, encouraging team initiative, and engaging in collective problem-solving.

Technology gives our maintenance technicians the ability to understand the consequences of their decisions. Now we can better integrate them as business partners, not just technicians turning a wrench, but as people helping us run the business. We're making better decisions all through, from the boiler room to the boardroom.

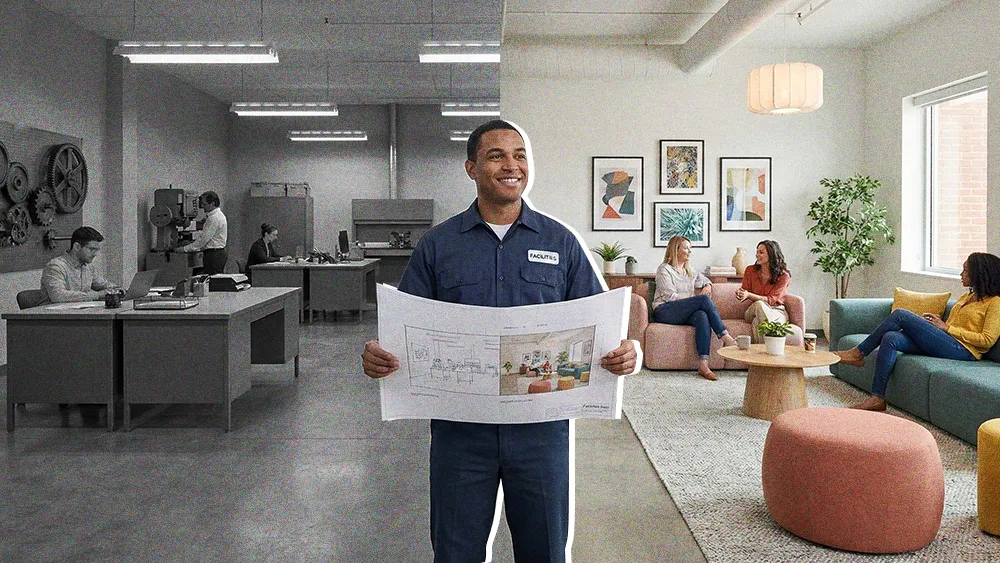

Technology is turning frontline workers into strategic thinkers. Without a corresponding evolution in leadership, however, that empowerment is limited. Now, a new kind of boss is emerging—one who shares the power and takes the blame. In an era where data is only as good as the culture it lives in, the "leader as mentor" model is arriving just when facilities management needs it most. Otherwise, strategic insights will never make it from the boiler room to the Board.

For an expert's take, we spoke with Clayton Mitchell, Senior Vice President of Corporate Facilities and Real Estate at Yale New Haven Health. With over three decades of executive experience leading large-scale infrastructure transformations at major institutions like Kaiser Permanente and Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Mitchell has long been a leader. But he's also a veteran of the U.S. Navy's Civil Engineer Corps. In many ways, his mentor-centric philosophy is still shaped by that rigid hierarchy today.

"Technology gives our maintenance technicians the ability to understand the consequences of their decisions. Now, we can better integrate them as business partners, not just technicians turning a wrench, but as people helping us run the business. We're making better decisions all through, from the boiler room to the boardroom," Mitchell says. Using AI-driven data to build a compelling business case for replacing a pump, for example, elevates their contribution beyond a simple repair.

A sea daddy: When that confidence grows, a technician’s job becomes more strategic, Mitchell explains. "Early in my career, a senior officer told me he saw greatness in me, but that I needed an advocate. In the Navy, they call that a 'sea daddy.' That made a profound impact on me. I want my people to feel that same sense of commitment and purpose, to know they are part of something bigger and that someone is in their corner."

The bridge house view: For a leader who builds this kind of self-sufficient team, the payoff is a new perspective, Mitchell says. "I talked about working myself out of a job, but it's really about working myself out of the job of supervision so I can devote my attention to more strategic, programmatic, and vision-oriented activities. To use a Navy analogy, I'd rather be in the bridge house looking out on the horizon, rather than being in the engine room trying to make things work. I get myself out of that engine room by making sure there are systems and processes to help the people down there."

Mitchell's inspiration is a deliberate framework built on three pillars: Vision, Communication, and Character. First, leaders must show their team "the art of the possible" with a strong vision, he explains. And, as a former battalion commander, he quickly learned that getting buy-in requires flexible, adaptive communication. "We have a lot of one-trick-pony leaders who only know one way to lead: with the hammer. I couldn't assume that any two people thought exactly the same way. In a one-on-one conversation, I had to find the channel they communicated on and connect with them there to be reasonably assured they understood what we're trying to do." But the final pillar, Character, is the engine that powers the model, he explains.

The Santa Claus clause: At its core, mindful leadership is about actively elevating other people. Mitchell demonstrates this through small, intentional acts of paying attention. For example, he recalls surprising a petty officer by asking about the nursing school aspirations she had mentioned on a career review form. "I told her that next time she pulls out her career review board, she'll see a little CM with a circle on it. I read every one of those. It's probably the most important thing that I read every day. It's like being Santa Claus, trying to figure out what everybody wants for Christmas and figuring out if there's a way to respond to that."

A confidence multiplier: During a pivotal evaluation before a deployment to Iraq, for instance, an evaluator expressed concern that Mitchell wasn't being authoritative enough. Here, he explains that real control is found in ceding it. "If a lieutenant is leading the operation and I don't 'take the con', that person's authority is elevated. By simply observing rather than assuming control, I can give them more power and confidence. The longer I do that, the less nervous they become, and it becomes their natural state." Later, when the admiral praised his team as "one of the most prepared units," Mitchell concluded that strength comes from creating a "sense of shared power," which he called a "force multiplier."

But empowering your team when things go right is one thing. The real test of leadership comes when things go wrong, says Mitchell. Only a foundation of psychological safety built on listening to frontline workers during moments of failure can make that level of initiative possible. "There's a strain of leadership that wants to be part of every solution and every success, but then doesn't own the failures. A true leader has to be willing to share the applause and shoulder the blame. If something went wrong, the first thing I do is ask myself if there was a process or system issue that I, as a leader, failed to address that contributed to the failure. Because at the end of the day, I own it."

The blame game endgame: After a crane inspection failed, Mitchell faced yet another defining test of this philosophy. In a room full of leaders looking to scapegoat one individual, he personally intervened to shift the culture from blame to accountability. "I stopped everyone and explained that after thinking about it, I could see five places where I personally could have intervened to prevent or mitigate the failure. The team responded that as the commanding officer, I shouldn't have to do that. But as the commanding officer, I am accountable for everything. I told everyone to go home and think about any place they could have intervened. The next day, we came back, and to a person, each had two or three things they could have done. Now we all owned it. That allowed us to take the pressure off the one individual who was woefully under-resourced and work collectively on a solution. That was a much healthier outcome than scapegoating."

Ultimately, a leader's impact extends far beyond quarterly metrics, Mitchell concludes. It's the lasting effect one has on others' lives and careers—an effect that can echo for decades, eventually creating a whole new generation of leaders. "My leadership style is predicated upon inspiring people. When you inspire people, you have an impact on them not only in that moment but also throughout their lives. The man who helped me was Captain Jack Dempsey. He inspired me, and I'm talking about him thirty-some-odd years later because he still has a very indelible impact on my life. I think the best leaders inspire people to be the best versions of themselves."